In August of 2021, EisnerAmper, a national public accounting firm, announced a strategic investment from private equity firm TowerBrook Capital Partners.

On April 11, 2022, Citrin Cooperman, another national public accounting firm, announced a deal with New Mountain Capital, a private equity group, to sell a majority of its shares.

On June 30, 2022, Cherry Bekeart, a top-25 public accounting firm, announced a “strategic investment” from private equity firm Parthenon Capital.

In February of 2024, Baker Tilly, a top-10 public accounting firm, announced a deal with private-equity firms Hellman & Friedman and Valeas Capital Partners.

And on March 15, 2024, Grant Thornton, the 7th largest public accounting firm in terms of global annual revenues, formally announced that it had entered into an agreement with New Mountain Capital, the same private equity firm that invested in Citrin Cooperman, to sell 60.0% of its equity. This impacted the US-portion of Grant Thornton’s business exclusively. At least until it didn’t.

What’s notable about this timeline is that both the size of the deals and the frequency with which they occur appear to be increasing rapidly. Prior to the EisnerAmper deal in 2021, public accountancies rarely dealt with private equity firms, and the deals themselves tended to involve much smaller firms.

For partners of the target accounting firms, these deals are generally seen as a significant boon. There’s a substantial lump sum payment for the buyout of the partners’ equity shares; an injection of cash to improve systems, technology, and hiring capabilities; and there’s an expectation—bordering on a promise—of rapid growth in the accounting firm’s future revenues.

These investments are usually presented in a positive light, even for the employees of the target company without equity shares. After all, the news is almost always broken by the partner class themselves, and if they’re happy, then the staff should be happy too! What gets glossed over in the press releases is the impact to the accounting firm over the next two to three years. As the size and scope of these deals increase, it can be increasingly difficult to determine who is pulling the strings behind the scenes, and who stands to benefit from these arrangements.

Today we’ll provide an overview of what the rise of private equity involvement in public accounting means to the non-equity employees; why PE firms are so excited about acquiring PA firms; and what the future holds for those firms accepting PE money.

What happens when a PE firm buys part of my public accounting firm?

Let’s take the recent New Mountain Capital purchase of Grant Thornton as an example. We have reports that NMC purchased roughly 60% of Grant Thornton, the arm of the firm in the United States. At a rudimentary level, the transaction unfolds as follows:

- NMC and GT US leaders meet to discuss the deal. If both parties express interest in the purchase, they will negotiate the purchase price. In this case, we have reports that NMC made a very generous offer such that GT US did not deem it necessary to shop around for better offers. A generous upfront offer indicates that the PE firm is negotiating in good faith, which is not always the case.

- GT US leaders took the NMC offer to the partner class. Because each of the GT US partners and principals is an owner of the firm, they get to vote on whether or not to accept the acquisition offer. In this case, we understand that the partners recognized this was a generous offer and overwhelmingly voted to accept.

- GT US must then drum up “shares” of the firm to sell to NMC. The easiest way to visualize this is to imagine that each partner owns ten shares of GT US, and they will each sell six of them to NMC. In return, they will receive a lump sum payment from NMC for the value of their shares of the firm. Using round numbers, if NMC agreed to purchase 60% of GT US for 60 million USD, and there are 1,000 partners with 10 shares each, each partner would receive $6,000 per share, for a total buyout of $36,000. They would also be left with four shares now valued at $24,000.

- NMC issues the payments to the GT US partners and receives the corresponding shares in return. As a majority shareholder, they now have significant control over decision-making and the direction of the firm. They also receive 60% of the annual profits of GT US going forward.

- The remaining GT US partner class now has less control over major decisions, but generally remains in control of daily operations. The partner class receives 40% of the annual profits of GT US going forward, which is then divvied up among the active partners. If in FY 2025, GT US earns operating profits of $50 million, NMC would receive $30 million, and each of the 1,000 GT US partners would receive $20,000.

In practice, the process is messier than presented above, and the payments to the partners are significantly higher. The important thing to consider when valuing the shares is that the GT US partners are forfeiting higher annual “salaries” (as partners, they receive a draw on residual profits, not an actual salary), for a large lump sum payment now. The value of this transaction to each partner is dependent on a number of variables, including their age, their time until retirement, their annual expenditures, and how much they anticipate the cash infusion from the PE firm will allow the accounting firm to grow quickly. Let’s look at two very basic examples of different partners for illustrative purposes:

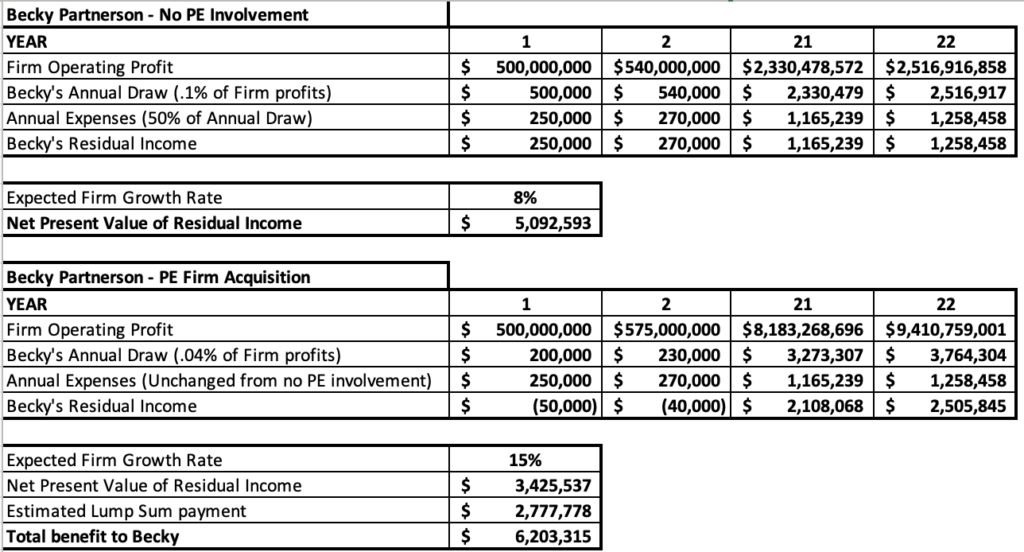

Partner A (Becky Partnerson): Becky is a newly minted partner, age 38. She anticipates retiring at 60 years old, meaning she intends to work as a partner for another 22 years. She has experienced some lifestyle creep since making partner, so her annual expenses account for roughly 50% of her annual draw. Before the acquisition, she made $500,000 per year, and after hearing NMC’s pitch, she’s optimistic about the future growth potential of the firm. She thinks the firm will grow by 15% each year for the foreseeable future, whereas before she expected it to grow by 8% annually. To consider Becky’s perspective, we’ll consult the following charts showing her career progression with and without the PE firm’s capital injection:

As we can see from the Excel summaries, Becky stands to benefit from the NMC acquisition if her assumptions are true. Over the course of the remainder of her career, she would earn almost $1.5 million USD less than she would without the PE firm’s investment, adjusted to today’s dollars. However, she would also receive the lump sum payment which we have estimated as 60% of the NPV of ten years’ worth of draws without PE firm investment. The $2.7 million USD lump sum payment would bring her the present value of her total earnings to $6.2 million USD, which is roughly $1.1 million more than had the PE firm not acquired GT US. Additionally, the lump sum payment will help her through the first four years post-acquisition, in which her annual expenses actually exceed her annual draw.

From Becky’s perspective, NMC acquiring GT US is a great deal. Her annual draw post-acquisition will be lower than it would without the PE firm deal for 16 years, but she’ll make more money over the course of her career, especially considering the lump sum payment. If the post-acquisition growth rate exceeds expectations, Becky stands to benefit immensely. However, if the growth rate fails to match her expectations, Becky may soon sour on the deal.

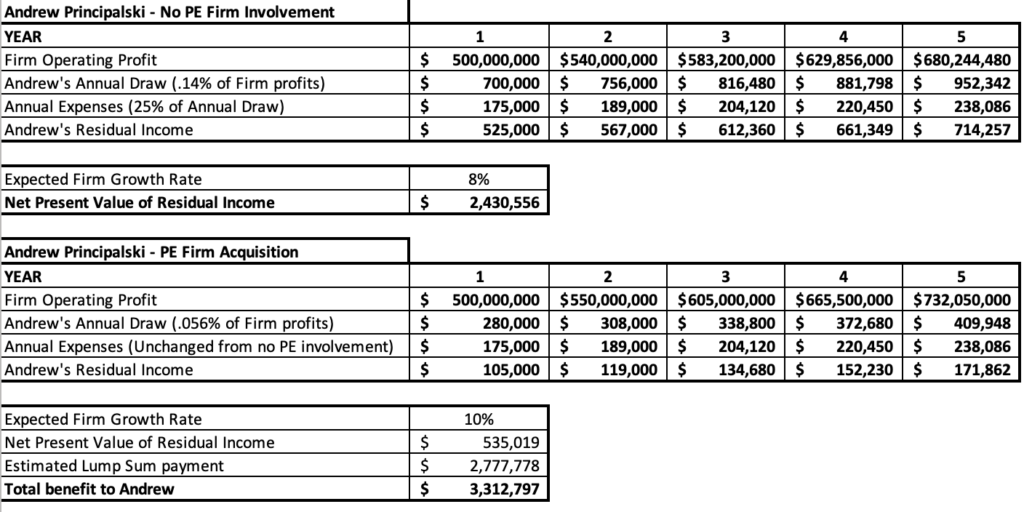

Partner B (Andrew Principalski): Andrew, at 55 years young, is a veteran of the public accounting games. He also plans to retire at 60, so he only has five years remaining in his career. Andrew is more frugal, and his annual expenses only account for 25% of his annual draw. Before the acquisition, Andrew made $700,000 per year. He’s not nearly as optimistic about the projected growth rates post-acquisition; he anticipates GT US will grow at 10% going forward. The following charts summarize Andrew’s perspective:

Andrew is probably excited about the PE acquisition. If his lump sum payment is identical to Becky’s, he would certainly vote in favor of the PE deal. Receiving a payment for the equivalent of 60% of 10 years’ worth of work is a major boon to Andrew, especially since he’ll only be working five more years. His residual income will be significantly lower for each of his five remaining working years, but the lump sum payment more than makes up for the loss.

Andrew is probably even more thrilled about the NMC acquisition than Becky. He receives a huge chunk of cash right now, and he doesn’t have to work for the five additional years for which he’s being paid. Because Andrew is only considering a five-year timeline, his pessimistic growth rate projection doesn’t have a significant impact on his take-home pay.

Additionally, if Becky and Andrew had pensions, which GT US partners did, NMC would buy them out of their pensions. For a new partner like Becky, this is likely a rounding error in her considerations. She’s unlikely to have a large, vested sum in her pension account, and with a 22-year career ahead of her, she can build her own “pension-equivalent” fund if she so desires. Andrew, on the other hand, is probably most concerned about the pension buyout. If his retirement calculations depended on receiving a fixed payment from GT US in perpetuity, he will need to balance the value of the pension buy-out against the cost of building his own pension-equivalent fund. We won’t dive into those details, but it is another wrinkle in the partners’ calculations.

Now that we’ve seen a rough sketch of how the PE firm acquisition process unfolds for the partner class, we need to determine what exactly the PE firm gets out of this transaction.

We are so many PE firms rushing to buy public accounting firms?

The experts at Wu-Tang Financial said it best: “Cash rules everything around me.”

To understand the motivation for private equity in buying public accounting firms, we need to first understand the PE business model. At their cores, PE firms are in the business of trading in businesses. Similar to a landlord with a real estate portfolio, PE firms scour the country for target businesses that would allow the PE firm to turn a profit upon selling it. How they turn the profit is critical, and usually falls into one of three categories:

- Passive Approach: The PE firm wants to purchase a business and hold it for 4 – 10 years or more. They generally approve of the target’s business model and leadership, and they believe the business will continue growing and remain profitable for the foreseeable future. They plan to purchase the business in part or in whole, leave operations to the original management team, and collect the annual cash flows to fund the PE firm’s operations. The PE firm will provide resources and guidance to the acquired business to the extent it makes them more profitable. When they sell it, they expect to have offers from a number of interested buyers.

- The Active Approach (Rehabilitation): The PE firm sees a distressed business with the promise of future profitability. Perhaps the target business has stagnated but operates within a lucrative industry. Perhaps the target business has a great portfolio of assets but management has been making poor decisions. Whatever the case, the PE firm believes the business can become a valuable part of their portfolio but requires some help to get there. The PE firm will provide ample guidance and resources, and will be more heavy-handed in exercising their control over business decisions and daily operations. There may be a sense of urgency as the PE firm tries to rehabilitate the business within a certain timeframe. How long they hold the business depends entirely on the target’s future profitability and the sales market.

- The Active Approach (Flipper): The PE firm sees a distressed business and doesn’t believe it would fit well within their portfolio for the long term. However, because the target is distressed, acquiring it can be a great value for the PE firm. They seek to purchase the business at a steep discount, enact some managerial and accounting changes to improve its outlook, and sell the business for a profit, typically to another PE firm. The PE firm will be very involved in the operations of the target business, and will seek to make it look as enticing as possible for another investor. The PE firm will ideally sell the business for a decent profit as soon as possible.

These approaches are not mutually exclusive. A PE firm may acquire a target with the intent of passively holding it for the long term, and quickly determine that the situation is actually hopeless. Perhaps the PE firm performed insufficient due diligence, or the target’s management was hiding a bunch of skeletons in the closet. Many PE firms will specialize in either the Passive or Active (rehabilitation/flipper) approaches, and will only employ the other methods when their preferred approach fails.

When it comes to PE firms acquiring public accounting firms, most rely on a more passive approach because public accounting firms are cash cows. Accounting firms that aren’t profitable cease to exist in short order, as they typically don’t have significant tangible assets to leverage for operational loans. Furthermore, many public accounting firms receive a significant portion of their revenues from annuity work, which provides a reliable revenue floor year over year. By acquiring a public accounting firm, the PE firm can expect dependable annual cash flows to cover their operational expenses. This allows the PE firm to fill their portfolio with riskier but potentially more profitable businesses, or alternatively build a portfolio of reliable cash producers.

Ultimately, the predictable cash flows produced by public accounting firms are a huge boon to PE firms, making them an enticing target.

The future of public accounting firms receiving PE cash infusions

We’ve demonstrated why accounting firm partners and private equity groups find PE investment mutually beneficial. The one perspective we haven’t considered is that of the lowly W-2 employee. As an associate, manager, or non-equity director, what should you expect if your firm is acquired by a private equity group? The results typically vary, but you can expect a few common themes:

- More resources, tools, and “sunshine.” A good PE firm wants its investments to perform well. As such, if they see any areas in your accounting firm where technology is outdated or inefficient, they’ll upgrade it. You will often be encouraged to use new software and applications. You will be told, regularly and gleefully, how these new tools benefit you and how much better things will be after the acquisition. Sometimes things are actually better!

- More scrutiny. Unless your public accounting firm was already fabulously profitable (and if so, did it really need outside funding?), the PE firm will want to keep an eye on operations. How aggressively they involve themselves depends on their perception of the target’s leadership and existing operating model. At the bare minimum, you can usually expect some new KPIs and a weekly newsletter extolling the virtues of the new partnership (see also: sunshine, above). In dire situations, you can expect the PE firm to bring in a bevy of management consultants and their own leaders to dramatically overhaul the business model a la the movie Office Space. Because accounting firms are usually profitable, the PE firms often take a lighter touch than they might with a struggling manufacturer, but be prepared for more scrutiny on discretionary expenses regardless.

- A season of generosity followed by an era of austerity. It’s important to remember that the driving force for the acquisition is money. PE firms acquire businesses with the expectation that they will provide profits, preferably both through their operations and through their eventual sale. Immediately after an acquisition, there is typically surplus cash in the accounting firm. Partners are receiving their windfalls, the PE firm is pumping in additional resources, and everyone is painting a rosy picture of the new relationship. This honeymoon period is intended to keep employees content and allow the PE firm to enact changes without dealing with massive attrition. If you’re looking to ask for a bonus, a promotion, or other favor, doing so immediately after an acquisition is a great time to do so. The fun will eventually end because fun is costly.

After the honeymoon phase, the PE firm will have a clear picture of what they purchased and the changes they want to make. As they shift their focus towards ensuring profitability, the excess benefits will wane. If they feel the firm is bloated, they may seek a reduction in headcount. Bonuses and raises may become more meager, and penalties for missing KPI targets may become stricter. Frequently, people that leave the accounting firm will not be replaced, resulting in leaner teams. There is no guarantee that the PE firm will become draconian overlords intent on squeezing out every last nickel from the corpse of your once-vibrant company, but these stereotypes exist for a reason. We recommend checking on the direction and mood of the company every month post-acquisition. Once conversations start to focus more on hitting KPIs and improving the bottom line than bolstering morale and technology, the fun is ending.

We fully expect interactions between private equity and public accounting firms to increase in the near-term. For the power brokers involved, the upside is immense and the downsides are largely shouldered by individuals with limited power (namely, aspiring partners and the non-equity class of employees). Furthermore, the companies that have taken PE money are generally reporting higher growth and profitability than before their acquisitions. This incentivizes accounting firms without PE money to prepare their companies for similar acquisitions or risk being left behind by PE-backed competitors. While Big 4 firms are not ideal targets for PE firms due to their size and complexity, even firms as large as Grant Thornton are viable targets. If Grant Thornton and New Mountain Capital achieve the growth they’re projecting, we expect the size and frequency of these deals to continue to increase.

For the aspiring partners and non-equity class of employees, we recommend career planning to determine how you will respond should a PE firm acquire your employer. Those seeking stability and a more relaxed working environment may consider leaving in the event of private equity involvement. However, those seeking to climb the corporate ladder quickly should consider riding out the post-acquisition turmoil, as these changes often create opportunities to impress leadership with your adaptability and work ethic. Check out our Career Planning section to determine what would work best for you.