Younger practitioners of the accounting arts may hear their managers talk about “engagement economics” without fully understanding what all that entails. We’re going to explain what the higher-ups mean when they discuss engagement economics; provide an example to demonstrate how everything works together; and explain why the whole process appears oddly complex. As with most features of public accounting, engagement economics is built on layers of woefully outdated structures, so your experience may differ from what’s presented here. What is universally consistent is how irrationally angry your manager will get when they find out you’re blowing their engagement budget by dumping time from another manager’s code into theirs. Unless you like irate emails with short-fuse demands, do be careful about where you put your time.

What does “Engagement Economics” Involve?

Engagement economics deals with how the firm and individual teams track the profitability of each client project. While the specifics can vary from firm to firm, there are some key terms that tend to be universal:

- Work in Progress (“WIP”) – How much revenue* the firm has accrued working on a client’s project, but not yet charged to the client. You may also hear this described as “unbilled time” or “the reason your manager is scrambling to issue bills at quarter end.”

- Accounts Receivable (“AR”) – How much money the firm has charged to the client, but not yet been paid. You may also hear this described as “outstanding invoices” or “the reason your partner is shaking down all of the clients at fiscal year end.”

- Out of Scope (“OOS”) – Any work performed that is above and beyond what was originally agreed to in the engagement letter (“EL”) or statement of work (“SOW”), which is the contract for services between the accounting firm at the client. OOS work is usually billed on a time and expense basis, similarly to how WIP is calculated. You may also hear this described as “the reason the engagement budget is blown” or “the reason the client is switching service providers” depending on how aggressive your partner is about pursuing OOS charges from the client.

- Engagement Budget – The maximum amount of money in the SOW that the client agreed to pay the accounting firm for services provided, not including OOS work. The engagement budget may also refer to the internal calculations that anticipate how many hours each team member will work on an engagement to reach the maximum agreed-upon payment. When a manager complains about a blown engagement budget, they’re saying that people are working more hours on an engagement than originally projected. This happens on 100% of engagements and serves as an excuse for managers to blow off steam on confused associates.

- Write-off – When you blow an engagement budget (i.e. when the sum of the WIP and the amounts billed to the client exceeds the engagement budget), the firm will take a write-off. In theory, this is simply the firm admitting that they undercharged for their work. In practice, this is a “big deal” that means the partners won’t have enough money to feed their families at fiscal year end. Depending on the size of the write-off, you may need permission from managing partners, senior leadership, or the Pope to correct the error. You may also hear this referred to as a “write-down.”

- Write-up – The opposite of a write-off, the write-up is a mythical event in which the team actually completes an engagement in fewer hours than anticipated. This is a cause for celebration, and may result in a pizza party if the write-up is significant.

- Engagement margin – This is the internal calculation of how much “profit” results from an engagement. Most firms will have a target margin for engagements, and usually these margins are ludicrously high when compared to manufacturing or distributing businesses. Expect accounting firms to target engagement margins of 30%-75% on most projects. The sum of these margins is what produces accounting firms’ partner distributions and employee bonuses.

- Realization rate – The amount of each dollar charged to the client that the accounting firm actually expects to collect. In theory this should be 100%, but in practice it’s usually lower. Sometimes clients are delinquent in paying their bills; sometimes the firm performs more work than it can reasonably charge to the client; sometimes partners short sell one engagement to get their foot in the door for a more profitable engagement later. To grossly simplify, the better the firm is at projecting engagement budgets and collecting AR from clients, the higher the realization rate.

Alright, that’s a ton of definitions, and you may be more confused than when we started. Let’s look at a simple example to tie the concepts together.

Engagement Economics in Practice

Partner Pete just sold a tax engagement to Client Carol to do her year-end tax provision. Partner Pete has been doing this work for Client Carol for the last five years, and has an efficient system in place. He sells these services to Client Carol for $50,000, which is the same as last year, despite 3.0% inflation year-over-year. Client Carol still complains that it’s expensive, because everyone in this song and dance must perform their role.

Partner Pete informs his engagement team (Manager Myrtle, Senior Sam, and Associate Adam) that they have won the engagement, and they’ll begin work immediately. He asks Manager Myrtle to draft the engagement budget and project the number of hours each of them will work on the engagement. Manager Myrtle considers delegating this work to Senior Sam, but he has little budgeting experience and is spending a lot of time training Associate Adam, who is new to the team.

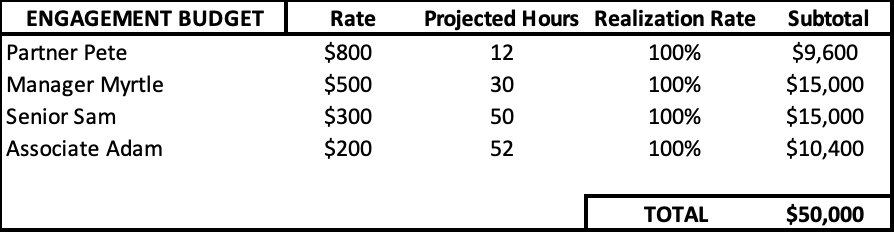

Manager Myrtle provides the following engagement budget to Partner Pete:

He agrees that it seems reasonable, despite not comparing it to last year’s budget, and they begin collecting the necessary information from Client Carol.

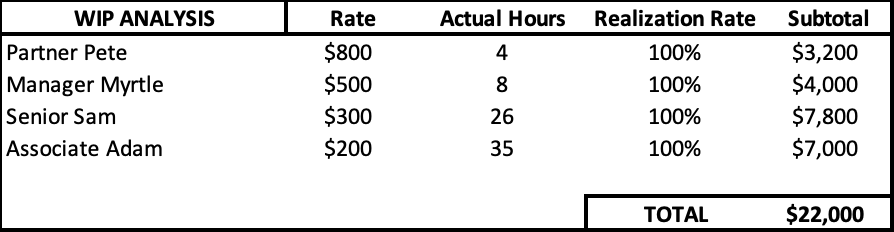

Two weeks into the engagement, Partner Pete asks for an update on the WIP. He also asks Manager Myrtle if they should issue an invoice to Client Carol. Myrtle performs a quick analysis on the status of the engagement:

Myrtle says they have $22,000 in WIP and suggests that they issue an invoice to Client Carol for the full amount of the WIP. Partner Pete asks her to prepare an invoice for $25,000, because Carol prefers to pay in 50% increments. Myrtle prepares the invoice, which results in a negative WIP (-$3,000 because the accounting firm has charged the client more money than they’ve accrued performing the work) and an AR of $25,000 (which will remain in AR until the full amount is collected from the client). At this point, the engagement economics look great. The firm loves negative WIP, and with a realization rate of 100%, it expects to collect all of the AR.

Manager Myrtle, being a wise and capable manager, then does a thorough analysis on the status of the engagement economics. She determines that they really aren’t halfway done with this engagement yet, and that Associate Adam has been charging more time to the engagement than she originally projected. She talks to Senior Sam and Associate Adam, who confirm that they’ve spent a lot of time reviewing materials and trying to understand what to do. Manager Myrtle encourages them to approach her with questions when they’re confused so that they don’t blow the budget.

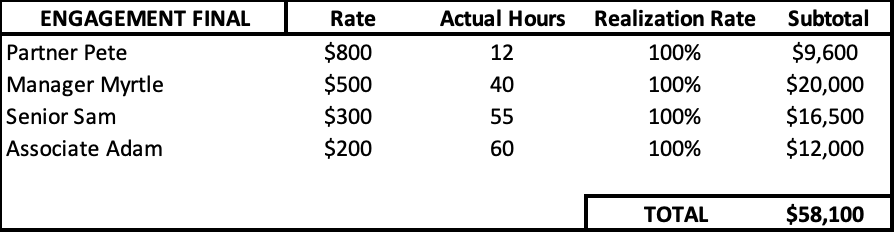

Senior Sam and Associate Adam are perpetually confused and begin asking Manager Myrtle for help. Two weeks later, the three of them finish the engagement, but Manager Myrtle worked a lot more on training her underlings than she expected. She sends the final product to Partner Pete for his review, and while she waits for his notes, she analyzes the engagement budget. It looks like this:

Manager Myrtle tells Partner Pete that they’ll have to take a write-off of $8,100 because they spent more time on the engagement than expected. He complains that this will reduce the engagement margin from the 50% target to 43%, and now he can’t afford to send his son to summer camp in Monaco next year. Myrtle comes to the dark realization that Partner Pete’s son is better traveled at 12 than she is at 35, but she deftly holds off the existential dread until after work. She sends the write-off approval request to Senior Partner Spencer, who chides Myrtle and Pete for poor engagement management. Myrtle knows this whole charade will repeat itself next month when they close another engagement.

Common Pitfalls in Engagement Economics

While our example is necessarily simple, scenarios like this one are common. It’s difficult to sell an engagement, project its profitability, and perform the work as expected for several reasons:

- Engagement prices are sticky. If the partner sells a project for $30,000 this year, the client will expect the price to remain $30,000 next year. The partner could risk increasing the cost of the project, but clients can also switch service providers. Selling new work is much more difficult and costly than maintaining an existing client relationship. Most partners will elect to keep things consistent rather than risk losing a client over a few thousand dollars.

- Turnover kills efficiency. In our example, Partner Pete had been doing this same year-end provision for Client Carol for five years. Over time, the engagement team should get faster and more efficient at performing the work, right? They would, if it was the same engagement team every year. Public accounting firms experience a lot of turnover, and new team members won’t have familiarity with the previous years’ projects. This means training people from scratch every year, despite the projecting recurring annually.

- The “cost” of performing the work increases. Most public accounting firms adjust their rate cards every year or so. This means that their internal accounting recalculates the cost of each employee to perform one hour of work. These numbers invariably go up over time, which means that WIP is accrued faster. This also means that to maintain the same engagement margin with higher internal cost rates, the same work must be performed in fewer hours OR the price of the engagement must be higher. We already know that partners don’t like to increase the price of an engagement, so it falls on the engagement team to be more efficient in spite of turnover.

You may have noticed that I put “cost” in quotes in the previous bullet point. While I could go on a 2,000-word diatribe about this topic, I’ll summarize my thoughts as succinctly as possible here:

Most engagements these days are “fixed fee,” meaning the client agrees to pay a flat amount for services rendered. Most internal cost accounting is “time and expense,” meaning the accounting firm calculates the hours worked on an engagement by each employee, multiplied by their internal cost rate (plus any related expenses like travel to the client site). Time and expense calculations imply variable costs, where spending more time on an engagement means it will cost the company more money to complete it.

Almost all employee costs to the accounting firm are fixed (employee salaries and benefits), meaning they can be accurately forecast at the beginning of each year. Whether an employee works for 2,080 hours this year, or 2,500, their cost to the firm should remain roughly the same. The mismatch between what the client pays the firm (fixed), what the firm pays its employees (fixed), and what the firm uses to analyze its engagement economics (variable), makes the whole engagement economics process complicated.

Whether a team collectively spends 50 hours or 500 hours completing the engagement, they’re taking home the same salary. In either scenario, the accounting firm is receiving the same amount from the client. The only difference is the internal accounting says completing the engagement in 50 hours provides a much higher engagement margin than completing it in 500 hours. But is it really? In both cases, the actual revenue is the same, and the actual costs are the same; none of the employees are receiving overtime pay and the client isn’t paying more for the extra hours.

The argument against this line of thinking is the opportunity cost of the employees’ time. If the employees spend 500 hours on an engagement instead of the 50 hours originally projected, that’s 450 hours they can’t spend on another engagement, right? To quote Brigadier General Anthony C. McAulliffe, “Nuts!” Partners aren’t going to stop selling engagements because their team is working too many hours on another client. If their team is swamped, they’ll beg, borrow, and steal resources from other teams to get the work done. The opportunity cost argument only works if there actually is an opportunity cost, and hell will freeze over before a partner turns down client work because her team is too busy.

Only a 376-word diatribe, not bad.

Summary

Engagement economics is the way in which an accounting firm tracks the profitability of each ongoing engagement. Every firm will have a unique methodology for accomplishing this task, including target margins and approval processes for situations that deviate from projections. As a manager, senior, or associate, your goal is to efficiently complete an engagement to the best of your ability.

Because of quirks in internal cost accounting, the whole process may seem needlessly complex. If you’re a younger employee thrust into engagement economics for the first time, seek out help from an experienced manager. Most firms will have shortcuts, workarounds, and loopholes to help improve the experience. The biggest thing you can do to help yourself is to understand what targets and goals the firm expects from each engagement and to regularly monitor the progress towards those goals. And when (not if) you blow an engagement budget, just relax. You’re now a member of a fraternity that includes every public accountant manager over the past 50 years. It will happen again next month.

*Calculated as the sum of the hours worked on an engagement by each employee, multiplied by the hourly rate of those employees, plus any associated expenses. This calculation is also referred to as “time and expense,” as it measures the work hours and related expenses incurred by the accounting firm in performing client services.