The majority of associates and senior associates in public accounting firms are in their 20s. Many are earning a living wage for the first time in their lives, and for the seniors especially, many will finally be able to save and invest significant sums of money. There are a number of high-quality personal finance blogs out there providing guidance to young employees on how to structure their budding stockpiles of wealth. Public accounting is unique enough that we think there’s value in reexamining the common “personal income spending flowchart” for new-to-senior-level associates. There are several instances where common advice doesn’t apply to PA employees, particularly for those subject to strict independence requirements.

Before we get into the specifics, the expectations:

- Our recommendations are based on personal experience. We are not financial advisors, and you should take everything we say with a heaping cup of salt.

- Our recommendations are based on you “betting on yourself.” That means you sincerely try to succeed in your career, even if you don’t want to be in public accounting long-term.

- Our recommendations are based on realistic career aspirations. If you believe you’re going from associate to partner in 7 years, you’re very likely going to be disappointed. Be honest with yourself about your abilities and goals.

Let’s talk money!

Order of Operations

Building real wealth takes a lot of time and some effort. It requires learning obscure knowledge about the tax system, and investments, and interest rates. There are sick, twisted people out there (like us) that find these topics delightful and entertaining. Sane people would rather learn about ostrich racing than the benefits of a Roth IRA.

The silver lining is that our preferred form of investing is largely “set it and forget it.” We support automating as much as you can and regularly reviewing your system to ensure it’s working. Things like having your credit card automatically pay off the entire balance each month minimize the amount of time you spend on maintenance. We also support using the spending flowchart (see above) to help you prioritize where your excess money should go. For instance, let’s say you’ve saved 6 months of monthly expenses in cash or cash-equivalent assets as an emergency fund; now, every additional dollar you want to invest should go towards earning the “free money” from your employer.

In summary, the “standard” order of operations for personal savings and investment are:

- An Emergency Fund (a chunk of change worth 1-6 months of your expenses for when life throws you a curveball);

- Free Money (Employer matches on 401k contributions, employer HSA contributions, other accounts where your employer provides money for participation);

- Eliminating Medium-to-High Interest Debt (credit card debt, some student loans, hopefully not a car loan but sometimes those too);

- Maximizing Retirement and Tax-Advantaged Accounts (401k, IRA, Roth variations of each, HSA/FSA); and

- Eliminating Low-Interest Debt/Investing in Brokerage Accounts/Saving for a Big Purchase (you have enough money that you deploy it where you find the most value).

Everyone should build an emergency fund and strive to eliminate high-interest debt. Where things get different for public accounting employees is in the “Free Money” and “Retirement and Tax-Advantaged Accounts” categories. For these, we’ll provide a summary of the standard use case and compare that to its value for an associate or senior associate.

Free Money – 401k Matching

Standard Use

401k matching is a common employee benefit among medium-to-large corporations, including public accounting firms. Usually it’s structured something like this:

- In 2024, you can contribute a maximum of $23,000 per year to a company-sponsored 401k investment account, directly from your paycheck. This money is put in the account before taxes are applied, meaning your taxable income for the year is reduced by the amount you contribute. You can then use the money you invested in the 401k to buy stocks, bonds, ETFs, etc.

- To encourage employees to contribute to their 401k (for totally altruistic reasons), employers may offer to match a percentage of your contributions. Let’s say the company offers to match the first 5.0% of your income you contribute to your 401k, and you make $75,000 per year. If you contribute at least $3,750 of your income, your company will put $3,750 of their dollars into your account. This matching contribution is in addition to your maximum personal contribution; if you contributed the maximum amount, your account would show $26,750 (your $23,000 contribution plus the company’s $3,750 matching contribution).

- The $3,750 portion that the company contributes is separate from your contributions until you are vested. Being vested means you’ve stayed with the company for a certain amount of time in good standing. If your company says the matching contributions are 100% vested after 2 years with the firm, the full value of these employer matches is yours to keep after 2 years of continuous employment.

For most people, contributing enough to their 401k each year to receive the full company match is amazing. It’s “free” money from your employer simply for participating in a tax-advantaged account in which you should always be investing.

Difference for Public Accounting

For public accountants, the calculus is a little more situational. Many PA firms structure their 401k matching programs like this:

- In 2024, you can still contribute a maximum of $23,000 per year, and it’s still pre-tax.

- Your PA firm offers to match 25% of the first 6.0% of your salary you contribute to the 401k. This is a convoluted way of saying that if you contribute 6.0% of your salary to the 401k, they’ll match 1.5%. If you still make $75,000, you’ll need to contribute $4,500 to have the partners chip in $1,125. While it’s still “free money,” you receive less and have to contribute more than someone with a 5.0% flat matching rate.

- Most PA firms use what’s called a “three-year cliff” vesting schedule. That means for the first 1,094 days of your employment, you are 0% vested in your firm’s contributions. On the day you reach your third year with the company, you cross over the cliff and become 100% vested in those matching contributions.

If you’re thinking to yourself, “Gee, that sounds like a long time to wait for a very little amount of free money,” congratulations. You have discovered why the value proposition for maximizing 401k matches in public accounting is lackluster at best. Not only do associates and senior associates receive a smaller match than those offered by other similarly-sized corporations, but if they don’t stick around through the three most challenging* years of their career, they don’t keep any of it. For most younger public accountants, a $5,000 signing bonus would be worth more than their employer’s fully-vested matching contributions after three years. The match is “free,” so it’s still worth pursuing if you expect to stick around for three years, but its value to young employees is low, especially if you’re doubting your career or firm choice. This is a long way of saying “Don’t lose sleep over forfeiting the company match before becoming fully vested if you can get an equivalent or greater amount as a signing bonus for switching firms.”

You should still contribute as much as you comfortably can to your 401k because it’s a tax-advantaged account. Just don’t believe that the matching contribution from the company is going to be substantial unless you plan to stay at the same public accounting firm for 5+ years.

What if I have access to a Roth 401k?

Rarely, public accounting firms will offer a Roth 401k option for employees. The difference between a traditional 401k (which we discussed above) and its Roth cousin is that Roth contributions are post-tax, while traditional contributions are pre-tax.

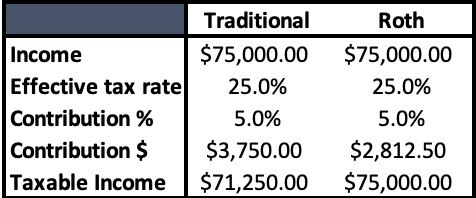

Let’s say you still make $75,000 per year. If you contributed 5.0% of your income to a traditional 401k, you would chip in $3,750 and your taxable income would be $71,250 because those 401k contributions are pre-tax. If you contributed 5.0% of your income to a Roth 401k, the contribution amount would first be taxed, then contributed to the account. Coincidentally, this does not reduce your taxable income for the year.

So why would anyone choose the Roth 401k option? With the traditional option, your taxes are deferred, meaning when you finally withdraw money from the 401k to spend it, you’ll pay income taxes at that time. Because you’ve already paid the taxes on your Roth 401k contributions, when you eventually withdraw money from the Roth 401k, you don’t have to pay taxes on it. This is especially helpful if you make a relatively low salary now and expect to make a relatively high salary in the future when you start withdrawing. These are round numbers for simplicity, but consider it this way: you can pay a 25% effective tax rate on your investments now, or if you’re wildly successful in the future, you would pay a 40% effective tax rate then. The calculus is different for every person, but common wisdom states this:

If you expect to have a higher income when you start withdrawing from your 401k than you do now, you should use the Roth 401k. If you expect to have a lower income when you start withdrawing from your 401k than you do now, you should use the traditional 401k.

There are exceptions to this guidance, especially if you’re on the early retirement track, so dig a little deeper before you select traditional or Roth if you have those options. Matching contributions for Roth 401ks can either be treated like a traditional 401k (pre-tax) or a Roth 401k (post-tax) since 2022. The guidance from the previous section still stands: unless your PA firm offers a very generous matching contribution that exceeds industry standard, neither the traditional nor the Roth matching contributions are going to be significant.

*Subject to debate, but the first three years of a PA career are undoubtedly tough.