Public accounting firms often rely on a common business structure called the “partnership model.” The partnership model intentionally creates two separate classes within the business: the equity-holding partners, and everyone else. The equity partners serve as business owners, while everyone else serves to support the business.

Most equity-holding partners aren’t in public accounting for the “love of the game.” This isn’t professional basketball, and Partner Pete isn’t the Michael Jordan of tax filings. The reason accountants stick around for more than a decade, toiling in the audit sweatshop alongside associates and managers, is for the chance at striking it rich when they become owners of the business. This is a career of attrition, and the people who can gut it out the longest are heavily rewarded for their efforts.

In the higher-tier business schools, we each receive a tattoo of the Friedman Doctrine on the third day of our MBA program’s orientation. We’re forbidden from showing it to anyone, but we are obligated to share Friedman’s wisdom with every person we meet: “The social responsibility of a business is to increase its profits.” Those who graduate at the top of their class get a corollary tattoo: “A business is only responsible to its shareholders.”

Public accounting partners are generally too smart to become MBAs, but they do benefit from the Friedman Doctrine just the same. It sounds cynical, but it’s important to state this plainly: the partnership model is a machine designed to enrich the equity partners. The equity partners have a duty to themselves and each other, as the shareholders, to ensure that the public accountancy increases its profits. As the shareholders, the equity partners are also entitled to any excess profit created by the business. This doesn’t mean that the “everyone else” class can’t make themselves fabulously wealthy from outside the ownership structure, but it does mean that they’ll be fighting the system every step of the way.

We’re going to take a brief look at the partnership model from the layman’s perspective. We’ll also dive into the unique benefits afforded to the equity partners, and how you, a special and extraordinary member of “everyone else,” can capture some of the scraps leftover from the partners’ feast.

A Brief Explanation of the Partnership Model from “Everyone Else’s” Perspective

Editor’s note: This section includes a somewhat scornful take on the partnership model. Please remember, this is a critique of the model, not the individual partners. In our experience, public accounting firm partners are smart, hard-working people with an above-average tolerance for the grind. We are not accusing any individual or group of individuals of avarice, deceit, or fraud. We are really enjoying the thesaurus today.

The partnership model is great if you’re a partner and not-so-great if you’re not. This is a result of two design flaws: 1. It’s (mostly) a zero-sum game, and 2. That game has a severe agency problem.

Zero-sum games require one party to lose so that another can win. Think chess: in order for you to win, you opponent has to lose. There’s no situation in which you can both end the game with more pieces than you started with. How are public accounting firms (mostly) a zero-sum game? Because any profits left over at the end of the year are distributed to the partners and to the employees. For each dollar the partners receive, there’s one fewer dollar available to distribute to everyone else, and vice versa. You glass-half-full types will counter with, “Well, yeah, but good bonuses make employees happy, and happy employees make profits go up! If profits go up every year, then we all benefit more than before!” This is adorably quaint reasoning that I’m not going to dispute here, except to say that’s why I included the “(mostly)” qualifier.

This leads to our second troublesome feature. Agency problems involve two parties: the principal and the agent. Agents are contracted by principals and are supposed to act in the best interest of the principals. However, agents may have the capacity to abuse this power for personal gain at the principal’s expense. In a perfect world, the principal and agent would structure their agreement so that when one party benefits, they both benefit. This way, the agent is always motivated to provide the best outcome for the principal. In reality, agents have a tendency to behave like selfish twits if there aren’t guardrails.

Public corporations have some protections in place to structure the relationship between employees and employers. Financial statements are publicly available, so each party has access to accurate information about the health of the company. Some employees have a separate group of agents advocating on their behalf in the form of a union. Major decisions are usually handled by the CEO (who answers to the board of directors), or the board itself (which answers to the shareholders). Employees can buy shares of company stock if they want to vote for members of the board of directors. The system isn’t perfect, but each party usually has recourse if they think they’re being hoodwinked.

In the partnership model, these guardrails are limited or nonexistent. Detailed financial statements are not publicly available for partnerships, so partners can access much more thorough financials than the employees. Public accounting doesn’t dabble in unionism, and that doesn’t appear to be changing any time soon. Major decisions are still handled by the CEO or the board of directors, but these individuals are almost always senior partners of the firm. The shareholders are exclusively partners. Non-equity employees have no representation, suffer from asymmetrical information, and cannot vote to hold decision-makers accountable. From the employee’s perspective, the agency problem is that they have no agent. Employees must rely on the partners to act in their best interests, and the partners are not incentivized to do so. Remember, this is a zero-sum game, and any profits that go to the employees are profits that don’t go to the partners.

In practice, the partnership model isn’t as harrowing as I described above. Partners aren’t actively trying to fleece their employees or hoard firm profits like the accounting dragons of yore. Employees can still earn a comfortable living, even if they never assume the mantle of partnership. But, employees should be aware that they are playing an unfair game. The partnership model is designed to benefit the partners, not the employees, so employees need to ensure that they advocate for themselves.

Next up, a palette cleanser. Let’s look at the partnership model from the perspective of the beneficiaries. The outlook is much rosier from this side of the buy in!

Benefits of the Partnership Model, a Partner’s Perspective

Bonuses and Profit Sharing

The most obvious benefit of being an equity partner is the bonus and profit sharing structure. Like everyone else, partner bonuses are often tied to the firm’s overall performance and individual accomplishments. Unlike everyone else, partner bonuses are typically massive. Let’s do some back-of-the-envelope math using a hypothetical company called Earnest & Youthful, LLP (“EY”).

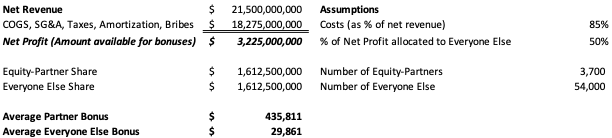

In 2023, the US branch of EY had roughly 3,700 partners, roughly 54,000 non-partner employees, and earned about $21.5 billion. EY isn’t obligated to release audited financial statements, but we can take an educated guess at their annual costs. Most public accounting firms aim to recognize at least 30% of each dollar charged to clients as profit. Let’s handicap EY a bit because they’re so large, and large companies tend to have more bloat than small firms. Let’s say EY earns 15% in profit on each dollar charged to clients. Let’s also be generous and argue that EY gives 50% of its profits to “everyone else” as bonuses. What would an average partner bonus look like in 2023?

In our rough-and-ready example, the average partner earns a bonus of $436k, while the average non-partner earns a bonus of $30k.

I can hear the associates and senior associates seething. You haven’t sniffed a bonus in the same area code as the average Everyone Else Bonus, and you probably won’t until you’re a seasoned manager. An experienced director or senior manager may see a bonus far in excess of that $30k, while associates would be happy to receive a $3k bonus. The range of partner bonuses is equally wide. Younger, scrawnier partners will earn bonuses significantly below those of the silverbacks at the top of the hierarchy. Still, when comparing partners to non-partners, the difference is stark. An equity partner’s profit share can easily be 10 times greater than that of an experienced manager.

Equity and Retirement

We’ve established that profit sharing can drop the equivalent of a new suburban townhome into partners’ bank accounts each year, but equity growth has the opportunity to lift partners’ families into higher social classes. When a lowly senior manager enters her chrysalis and emerges later as a newly minted partner, she must “buy in” to the firm. Buy ins are structured differently at each accounting firm, but it’s best to think of it like a short-term mortgage. A new partner takes out a loan (from the company) against the equity shares they receive, and each year, they pay off a chunk of that loan. Most partners pay off their buy in within three to five years, at which point, they are fully vested owners of the firm’s equity.

Over time, partners accumulate more firm “shares” or “units” or “fun-bucks,” increasing their equity holdings. By the time a partner is ready to retire, she may have a healthy basket of equity shares in the firm, and the firm will buy those from her when she leaves. The exchange rate on equity shares is dependent on a variety of factors, but it almost always goes up. So whatever rate the partner paid to buy into the firm is practically guaranteed to be less than the rate she receives when she’s bought out. Add in the additional shares she’s accumulated over the course of a 20-year career as partner, and the retirement buyout boon can easily clear several million dollars.

Buy outs also occur when public accounting firms are acquired in part or entirely by another firm, or a private equity firm. We discuss the structure of acquisition buy outs here. In short, these are wonderfully lucrative paydays for partners, and a great time to ask them for a favor.

In addition to being bought out of equity shares, partners often receive other fun retirement benefits. Some firms still offer pensions, which are usually structured such that post-retirement, a partner receives a portion of her average annual pay for the remainder of her life. Some firms will bring partners back as advisors or consultants at a much higher hourly rate than they were paid before. It’s the firm’s way of saying, “Thank you for your decades of service. You’re too old to represent us, now please go be wealthy somewhere else.”

Hidden and Not-So-Hidden Perks

Being an equity partner is mostly about the money. As I said at the beginning, the sickos that have the brains, grit, and divorce attorneys to make partner aren’t in this for the love of the game. They’re grinding to earn a wealthy, comfortable lifestyle for themselves, their family, and their heirs. That said, there’s also some pretty sweet perks that come with making partner in a public accounting firm.

First, the obvious things: Partners get access to nicer offices (when new associates aren’t squatting in them because the hoteling desks are full), personal assistants, expense accounts for wooing clients, and frightening numbers of hotel and airline points. Many also enjoy benefits like gym memberships, premium health insurance, and corporate retreats in exotic locations. Firms provide access to a battery of lawyers, specialists, concierges, and more, so that partners can spend more time earning money for the business.

Next, the subtle perks: Partners can influence the direction of the firm, decide who should be added to their ranks, a build their own fief. Senior partners and those with political savvy determine who should lead the company and where the firm should spend its money. When a director is gunning for promotion to partner, existing partners act as the gatekeepers. And with limited exceptions, partners are given broad leeway to handle the hiring and firing decisions for their teams. If Partner Pete wants to hire his cousin, his sister, and his buddy from grade school to help audit his clients, he’s not going to encounter much resistance. Especially if they all have different last names.

The hidden perks revolve around the level of networking partners can achieve. Partners have professional relationships with CEOs, executives, boards of directors, and a menagerie of corporate bigwigs. Having access to important people with business clout opens a lot of doors to partners, both as a representative of the accounting firm and as an individual. If Partner Pete desperately wants to get his daughter into Yale, but her grades aren’t cutting it, he has options. His income affords him the best tutors. His equity affords him the means to pay for her tuition. And his network affords him a letter of recommendation from the CEO of an influential client, who just so happens to be an Eli.

Rage for the Machine

Public accounting firms enrich their equity-holding partners through a combination of financial rewards, perks, and influence. What’s important to remember is that partners worked hard to earn and maintain these benefits, and they naturally want to support the system that provides them. The partnership model is the golden goose, and you’re never going to see a partner act or vote to endanger the status quo.

If you’re not a member of the partner class but you want to benefit from the firm’s largesse, the best approach is to align your incentives with the partners’ incentives. Find out what metrics the partners care about, and make sure you hit those so your rank, salary and bonuses increase quickly. Find a partner who is willing to be your mentor, and make sure you join them on as many business trips and client meetings as you can so you grow your professional network. Learn about the benefits the firm offers and make sure you use every one that makes sense so you know how to operate within the system. There’s no denying that you’ll feel like a sell-out at first, but you’re already playing an unfair game by working in the partnership model. You might as well learn how to play well with the deck stacked against you, so that if you do become a partner, you’ll be ready to reap the full suite of benefits. Besides, you already sold out when you decided to become an accountant. Embrace the beige.